The Mayo Clinic with funding from the feds (SAMHSA) has weighed in on the issue of early recognition and intervention for possible symptoms of mental disorders by issuing a list of warning signs that should be seen as red flags by parents –Culled from a Mayo study of 6000 child/teen cases of various disorders.

Here’s the list….

If your child has any of these 11 warning signs, he or she may have a mental health disorder and should be referred to treatment as soon as possible:

Feeling very sad or withdrawn for two or more weeks

Seriously trying to harm or kill themselves, or making plans to do so

Sudden overwhelming fear for no reason, sometimes with a racing heart or fast breathing

Involved in multiple fights, using a weapon, or wanting badly to hurt others

Severe out-of-control behavior that can hurt the teenager or others

Not eating, throwing up, or using laxatives to lose weight

Intense worries or fears that get in the way of daily activities

Extreme difficulty in concentrating or staying still that puts a teenager in physical danger or causes school failure

Repeated use of drugs or alcohol

Severe mood swings that cause problems in relationships

Drastic changes in behavior or personality

According to Mayo…”This data substantiates what we already knew, that there are warning signs of significant mental illness, but children and adolescents aren’t getting help because health care providers don’t share the same language,” said Dr. Abigail Schlesinger, medical director of outpatient behavioral health services at Children’s Hospital Pittsburgh.

READ THE WHOLE ARTICLE.

This excerpt from Victoria Costello’s memoir, A LETHAL INHERITANCE, first appeared in NAADAC NEWS, the magazine for addiction professionals.

When spoons began to disappear from my mother’s silver chest in the late 1960s, neither Mom nor I suspected my younger sister Rita’s dope use. It didn’t dawn on us that heroin had be mixed with water and cooked over a flame before it was injected. At that time, my friends and I smoked pot regularly, and, we had also tried psychedelics, mushrooms, and acid — tried being the operative word. Rita went farther and did it much faster, and more overtly. She flew through pot and discovered barbiturates, speed, and cocaine. Heroin was too pricey without help from an older boyfriend, but by the time she was 16, it had nonetheless become Rita’s drug of choice. She started stealing to get it: Mom’s wedding band was one of the first casualties; soon, cash could no longer be left in a drawer or purse.

This was before drug rehab as a concept had entered the American cultural lexicon, certainly that of the suburban northeast, leaving my mother baffled and ashamed at the behavior of her prettiest, once the easier of her two daughters.

When President Richard Nixon declared his war on drugs in 1971 — a war that has been hopelessly lost in the four decades since — it did one constructive thing by creating a new and favorable climate for research into the causes of addiction. This research gave birth to the field of drug rehabilitation, and out of that treatment came the theory of self-medication — the idea that addiction comes about because people are attempting to alleviate the distress of preexisting mental disorders. The concept had come originally from Freud, in 1884, after he noted the antidepressant properties of cocaine.

This theory immediately caused a storm of controversy because it challenged views then held by the medical community and law enforcement that attributed drug abuse to peer pressures, family breakdown, affluence, escapism, and lax policing. For the first time, the nation’s newly minted white middle class drug addicts (typified by my sister) were joining their less affluent urban counterparts, who were already populating U.S. jails and hospitals. Junkies — hippies, rich and poor, black and white, addicts and alcoholics — constituted an equal-opportunity mental health crisis for public health doctors on the front lines of treatment in big-city hospital emergency rooms.

The father of the self-medication hypothesis is Edward J. Khantzian, a founding member of the Psychiatry Department at Harvard’s Cambridge Hospital. Khantzian, writing in 1985, believed addicts weren’t victims of random selection but instead had a drug of choice: a specific drug affinity dictated by “psychopharmacologic action of the drug and the dominant painful feelings with which they struggle.” For example, he observed the energizing effect of cocaine and other stimulants in response to the depletion and fatigue of addicts dealing with preexisting depression. In his patients who abused opiates, Khantzian noted the calming effect of heroin on the addict’s typically problematic impulsivity.

The idea that human psychological vulnerabilities had anything to do with addiction was a brand-new piece of the puzzle, and it reflected Khantzian’s psychoanalytic background as much as his clinical work at the Cambridge Clinic. As a clinician, he saw the important roles played by what he called the damaged “ego and self structures” in his addicted patients. He then identified the following four common areas of psychological problems that led his patients to addiction: a lack of affect (low emotional expression), damaged self-esteem, inability to form and maintain relationships, and lack of self-care.

Decades later, Khantzian’s hypothesis is accepted medicine within the mental health field. Psychiatrist Allen Frances, in his review of a 2009 textbook edited by Khantzian (in the American Journal on Addiction) titled “Finding Hope Behind the Pain,” referred to the “simplicity and beauty of the self-medication hypothesis,” and “its usefulness in the clinical situation.” While Khanztian’s theory is accepted by his peers, a broader cultural understanding of the implications of this theory for individuals with undiagnosed mental disorders who may be self-medicating has lagged far behind.

Which comes first?

Is it the chicken or the egg; the mental illness or the addiction? This fundamental question remained unanswered up until the 1990s. In 1992, with a first-of-its-kind national survey of the state of the nation’s mental health called the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), scientific understanding of comorbid addiction and mental illness went mainstream. The NCS evaluated 8,098 average Americans, ages 15 to 54, interviewed in face-to-face home settings by trained laypersons — making them far less able to lessen or deny symptoms and patterns.

Among the striking results of the NCS survey: 45 percent of those people with an alcohol-use disorder and 72 percent with a drug-use disorder also had a least one other mental disorder. Perhaps more important at a time when the self-medication theory was still under attack, the NCS survey provided a concrete and comprehensive answer to the chicken-and-egg question about addiction and mental illness.

So which is it?

The NCS showed that when an alcohol disorder accompanied another mental disorder, the alcohol abuse began after the individual was suffering from symptoms of the other mental disorder, usually a year or more after. Not including other forms of substance abuse, the most common preexisting mental disorders reported among those interviewed were anxiety, depression, and, for men, conduct disorders.

When an updated NCS survey was done with a new group of ten thousand people in 2002 (called the NCS-R, for “replicated”), its findings were strikingly similar to the first. Faring worst by age group in the 2002 numbers were 36- to 44-year-olds, among whom 37 percent had anxiety disorders and 24 percent had mood disorders in addition to their alcohol abuse issues. Depressed women in their 30’s and 40’s have a 2.6 greater risk for heavy drinking, compared to those without major depression. It occurred to me as I read these numbers that age 30 to 44, when comorbid disorders are highest, are also women’s prime childbearing years.

Too late for so many

My sister Rita died at 38, a year after a heroin overdose left her in a coma for several days. While packing for a move not long ago, I found a letter I’d received from Rita, written during her first stint in Rockland County Jail for robbery a decade earlier, dated March of 1982:

I should have known I was heading for trouble again. I was having black-outs from small amounts of liquor (small amounts for me). But I went on another drinking binge and now I’m back here again. I guess I’ve hit the pits this time. I just finished speaking to a woman from the jail ministry. She’s quite sure that God brought me back here to save my life or try again. She may be right. I just feel really bad now that I won’t be home for Easter when you come. So much for all that. Meanwhile pray for me, forgive me for letting you all down, try to talk to Mom for me and take care of my beautiful nephew. Love, Rita.

Back then, I suppose I went no farther than thinking that Rita and others like her were weaker than I was in some fundamental way. Science now illuminates the finer points of the unequal inheritance of predispositions to addiction even in the same family, as well as the debilitating effects on those who carry the heaviest genetic load of growing up in a culture of self-medication. Simplifications like personal weakness simply don’t cut it anymore. It’s time for the culture to catch up with the science and practice of recovery.

From the book A Complete Idiot’s Guide to Child and Adolescent Psychology, coauthored with child psychiatrist, Jack C. Westman.

For several years now, critics of our educational system and parenting culture have been saying that American children and adolescents have too high an opinion of themselves. Actually, if you understand the source and definition of true self esteem, based on the self respect that emanates from external reality—not internal fantasies fed by well intentioned parents showering their kids with unearned praise—the latest research shows that our kids are sorely lacking in self esteem. The same studies reveal this to be an issue with special significance for tweens and their parents.

That’s because, when measured by psychological researchers, self-esteem is highest in preschool and lowest at the start of junior high school. Why? One view says the transition from elementary to high school is when children fall from a secure social position to a new unfamiliar one, and find themselves at the “bottom of the pecking order.” Parents can help their tweens navigate this difficult transition by understanding the source of authentic self esteem.

In a study of 2,000 low- to middle-income children living in the greater Detroit area, 25 percent of 9- to 12-year-olds had negative self-esteem. Their negative views of themselves showed up on all three scales measured: academic competence, social acceptance, and global self-worth. On each scale, 5 to 10 percent more girls than boys displayed negative self-esteem.

Understanding Authentic Self Esteem

Self-esteem and self-respect may appear to be synonyms, but as child psychiatrist Jack Westman points out in our new book, The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Child & Adolescent Psychology, they are not. A child’s self-esteem, Westman explains, can be low or high based on a fantasy he holds about himself, whereas self-respect is based on reality. You can have high self-esteem, and still be a selfish, inconsiderate person.

Kids who have been “spoiled,” whose parents consistently tell them that they are smarter, more creative, athletically gifted, and all around superior to others, can have high self-esteem. But this form of self esteem crashes when they are frustrated or don’t get the sort of approval they have come to expect.

In contrast, self-respect is having a good evaluation or judgment of yourself and having that view validated by realistic accomplishments and experiences with other people. Self-respect gives rise to authentic high self-esteem. This internal feeling is based on external reality.

Because these two words have been conflated in general use, we’ll refer to self respect (as we’ve defined it here) as self esteem but please understand that we are referring to the authentic meaning of this over-used, misunderstood term.

Why Does Self Esteem Matter?

Authentic self-esteem in children is important for a child’s emotional, social, and—now the research makes clear—also for her intellectual development. Sources of self-esteem include the following:

A child’s innate temperament helps shape her self-esteem. Easy, friendly temperament children tend to develop more self-esteem than children with difficult, inhibited temperaments.

When parents are willing to discuss household rules and discipline with them, their children’s self-esteem rises. A child then internalizes the message that she is important enough for her opinions to be heard.

Parents’ consistent warmth, affection, and involvement with their children builds self-esteem. A hug sends the simple message: “You are important to me.”

Self-esteem also comes from the peer comparisons a child makes and approval or rejection she experiences from peers.

Self-esteem comes from a child’s emerging “belief system” which can be seen as an accumulation of all of the preceding.

For more on the emotional-social, cognitive and moral development of children from zero to age 18, with all the latest science made clear and practical for parents, get the just released Complete Idiot’s Guide to Child & Adolescent Psychology, coauthored by child psychiatrist and national family advocate Jack C. Westman, M.D. and Victoria Costello, who blogs at http://www.mentalhealthmomblog.com

Originally posted on Mental Health Mom Blog, May 2015.

You caught your teenager with pot in her possession, or you got wind of its distinctive aroma in her room. Let’s say you immediately confronted her about it; perhaps you punished her, too. Still, your suspicion is that her use continues.

Should I worry? In brief, if your child is age 16 or younger, and /or there’s a history of mental illness in your family, you have good cause to be concerned.

According to the University of Michigan’s annual Monitoring the Future Survey, marijuana use by American adolescents, especially eighth and tenth graders, is trending upward for the third year in a row, reversing a decline tracked since 1992. Two other even more worrisome trends were reported in the survey. The age of first time marijuana users is dropping, and fewer teenagers believe there are health risks associated with their use of marijuana.

That these trends are present when so much existing scientific research points to the complicity of marijuana in triggering first episodes of psychosis in teenagers is terrifying. Or it should be.

One possible reason for the apparent widespread ignorance by teens (and their parents) may be the media’s general failure to distinguish between adolescents and adults when they report on marijuana use and its dangers. This type of oversimplified coverage has increased as medical marijuana is legalized in some states, and as state and local campaigns rev up to give marijuana the same legal status as alcohol.

Pot and Psychosis

Before we jump into pro or con camps on such issues, it behooves us to take a closer look at the science. It is true that the relative numbers of teens who smoke pot and develop psychotic symptoms is relatively low; in some studies it’s put at 3 percent. But the risk then goes up to 10 percent or higher for those teens who are at a genetic risk for psychosis, that is, those who had a relative with a psychotic disease like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Which brings us to the other equally large obstacle for anyone personally trying to confront this issue. How are parents to assess their teenager’s risk when they don’t know their own family mental health history?

The reason for this lack of basic information about our ancestors, i.e., parents, grandparents and great-grandparents mental health has everything to do with the centuries’ old stigma associated with mental illness. Plus, the lack of proper diagnoses and treatment for these illnesses which while not so great today was far worse in past generations.

Not having this information necessarily turns us into amateur forensic psychologists. Was your great aunt’s fear of leaving the house just eccentricity? Was grandpa’s death at 28 really an accident? Or may there have been other factors at work in these or other dark family episodes that have been largely swept under the rug–as turned out to be the case in my family.

I wondered what I might have done differently after finding pot hidden in Alex’s bedroom when he was 14 had I had known how dangerous it was going to be for him. Certainly, I got angry. I grounded him for a month. But, to be honest, at the time I thought Alex’s marijuana smoking was the least of our problems. More troublesome, I thought, was the fact that he hadn’t done his homework in recent memory.

For more information on teen drug use, go to the University of Michigan MONITORING THE FUTURE SURVEY.

There’s nothing more beautiful to me than a little boy’s exuberance. But as the mother of two now grown sons I still get the chills thinking about living with and attempting to keep both of them alive and on track from age 14 to (if I’m honest) 21. One question that bedevils parents dealing with a child or teenager’s chronically bad and/or alienated, depressed behavior is how to know whether he’ll simply “grow out of it.” The answer is probably yes, most do. But for a significant minority of children 8 to 18 (6 to 16% of boys, 3 to 9% of girls) the “it” in question may fit the diagnosis of “conduct disorder.” Then watching and waiting is not enough.

Starting a decade ago, I took this question on as a parent and science writer. I remember voicing concern to friends about my first born Alex during the period when he was using drugs, “tagging” and opting out of school and them responding by saying I shouldn’t worry; it was normal “acting out.” It would pass. They were wrong. I was foolish not to get better advice and act sooner. A wait and see stance when a child is hurting badly turns out to be potentially very dangerous example of a parent sticking her head in the sand. The research about what can easily be called an epidemic of conduct disorder in boys is sobering. One of the leitmotifs arising out of a number of the studies I’ve seen is a warning cry from researchers (albeit couched in careful clinical language) that, while the vast majority of kids grow out of their early childhood emotional and behavioral challenges, an important minority do not get better “on their own.”

Those at highest risk are living in households where there are other serious mental health problems present. Some chilling findings have emerged from multi-generational family studies to demonstrate that when antisocial behaviors begin early in younger boys [psychologists call this “childhood-onset conduct disorder”] the boys do much worse as they age compared to those who begin showing antisocial behaviors later in adolescence. When followed to age twenty-six, the young men in a New Zealand study who had childhood-onset conduct disorders were found to have worse mental health problems. They had more psychopathic personality traits, substance dependence, financial problems, work problems, and drug-related and violent crime, including violence against women and children.” But not all of them went this route. So, again, how can you predict which ones will do this badly?

Researchers looked into this retrospectively, and found that the risk factors in their childhoods that best predicted the children who would make this negative slide from misbehaving boy to delinquent young man had little to do with the child himself, and everything to do with what was going on in his family.

[Here is more information about effective treatments available for childhood and adolescent conduct disorder.]

According to Duke and Kings College London Psychiatric Institute reseracher Terrie Moffitt: “A family history of mental health problems; alcoholism, drug addiction, ADHD, or antisocial personality, is a very accurate way to predict which youngsters who have conduct problems will grow out of them, versus which will go on to develop a more serious prognosis as young adults. Of those kids with [such a] family history, over 75 percent had persistent conduct problems that lasted into adulthood.”

Moffitt acknowledged that parents with these sorts of problems are often resistant to entering family therapy or a parent training program. However, they point out that the predictive value of this data can help social workers and mental health providers when they encounter such children-or when an agency is forced to intervene after a report of maltreatment surfaces in such a family. As if that’s not bad enough, the news from researchers looking at childhood conduct disorders gets even worse.

The bad behaviors of these young boys doesn’t just put them at risk for anti-sociality, criminality and jail time in their young adulthood. It can also spell early psychosis. I’ll write about that in a follow up post. When I did finally get help for Alex – after he failed the eighth grade and got caught with drugs – it included a six week wilderness therapy trek for him with family therapy and individual therapy for me, including a long delayed treatment of my lifelong depression. Fortunately Alex was still young enough for it to make a difference. But it wasn’t just Alex that had to change behaviors. I had to confront my own substance use and the excess of household chaos caused by my divorce and subsequent upheavals that occurred during the years directly proceeding Alex’s descent.

Here is more information about effective treatments available for childhood and adolescent conduct disorder.

As mothers (and fathers) we are constantly monitoring our children to assess their well-being. After all, we know them better than anyone else. But do we always know the signs of problems that could escalate to a full blown mood or psychological (cognitive or behavioral) disorder? There is often a long lag time between the first sign of “trouble” we may notice in a child, and the point where a formal consultation is warranted. The following self-tests are not designed to replace an evaluation by a mental health professional. They are offered to provide a first step to help a parent answer the question “Could I be?” or “Could my child or spouse have?” Yes, some are about you…others concern a child or spouse. That’s because mental health is a family affair. So are mental disorders. And so is recovery.

Remember that with psychological disorders the primary symptoms are behaviors–a change in behavior or mood or a lack of behavior (walking/talking/having friends) which occur by a certain age or developmental stage. I highly recommend keeping a written log of any such symptoms you may learn about by taking one or more of these inventories. Then bring your log with you to your appointment with your pediatrician or mental health professional.

The following links go to Organized Wisdom, a website written by health and mental health professionals.

This free test will help you identify warning signs of attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to discuss with your doctor. ADD and ADHD are conditions generally diagnosed in school-aged children, but teens and adults can suffer from them, too. This quick quiz will identify whether you’re exhibiting symptoms of ADHD, as detailed in the DSM-IV criteria.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is an extremely common, treatable condition that affects children’s attention and behavior both in and out of school. This quick quiz will identify whether your child is exhibiting symptoms of ADHD, as noted by the DSM-IV Criteria for ADHD.

3) Does my child have Oppositional Defiant Disorder? (sometimes called Conduct Disorder)

The questions that follow may help you spot oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) in your child, a condition that often occurs along with ADHD. This quick quiz is based on a portion of the Vanderbilt Rating Scales developed by Mark L. Wolraich, M.D. Be sure to discuss the results with your child’s doctor.

Did you know that most people with depression don’t recognize the warning signs, and never seek treatment? The best way to tell if what you’re feeling is depression is to use a checklist or assessment to see if you’re experiencing common symptoms. This quick quiz has been adapted from the highly respected Burns Depression Inventory created by David D. Bums, M.D., author of Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. Find out if you’re genuinely depressed.

Click to read the NEW NIMH Child & Teen Depression Fact Sheet

This quick quiz is based on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, one of the many screening tools that doctors and mental health professionals use to help identify bipolar disorder.

6) Could my spouse be Bipolar?

If you’ve ever wondered if your spouse could have bipolar disorder, this quick quiz may help. These questions have been adapted from the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, one of the many screening tools that doctors and mental health professionals use to help identify this condition.

7) Do I or a loved one have Borderline Personality Disorder?

More than 6% of the U.S. population will experience borderline personality disorder (BPD) at some point in their lifetimes. This quick quiz, based on the diagnostic criteria (DSM-IV) for BPD, may reveal if you’re showing the signs. Discuss the results with your doctor or mental health professional.

8) Is Someone I Know suicidal?

Suicide is preventable. If you have a friend or loved one with suicidal thoughts you owe it to them to try to help. Take our quick quiz to help you determine whether your spouse, relative, or friend is showing the warning signs.

Take this quick quiz if you’ve ever wondered, “Am I an alcoholic?” While small amounts of alcohol can have a beneficial effect on health, heavy drinking hurts your body, your mind, and your relationships. Find out if it might be time to get help.

Many experiences in life are stressful, some more than others. The following quiz, based on the Life Stress Inventory, also known as the Holmes and Rahe test, rates the stressful experiences you’ve had over the past year, and calculates your risk of developing a stress-related illness. This comprehensive quiz may take up to five minutes to complete. Answer each question honestly, based on what is currently happening in your life, or what happened over the past year.

ONE MORE…A Self Screening for Symptoms of Early Psychosis on the website of U.C.S.F.’s PREP Youth Clinic.

Originally Posted on July 22, 2013

I just tried a new online tool from Mental Health America called “How’s Your Mood Today?” which can help you evaluate whether things you’re thinking, doing, or feeling may in fact be symptoms of one of these four, perhaps not yet diagnosed, mental disorders.

Because of the continuing stigma about mental illness, one of the hardest things for many of us is to seek help for bonafide symptoms of depression, and anxiety — or one of the other two less-common disorders, PTSD or Bipolar Disorder. Here’s a simple way to find out if some bothersome or distressing symptoms you may be experiencing add up to a possible mental health disorder for which you should seek help — right away!

Before recommending it to you I tried it myself. After filling out the quick multiple choice questionnaire (truly took 90 sec) with answers that described the me of 12 years ago — before I began using antidepressants to treat my (lifelong) depression and anxiety disorder –I found the (instant assessment) that popped up to be very accurate. It described me as someone displaying symptoms of moderate depression and therefore in need of professional evaluation and possible treatment. One thing I like very much in this test is its emphasis on identifying symptoms that interfere with some aspect of your life.

If you haven’t yet found the courage and/or financial resources to actually go to a clinic or public mental health department for such a screening, taking this test would be a solid first step to give you a better idea of how serious your symptoms are right now.

Here’s how MHA describes the tool:

Mental Health America provides the only online test that screens for depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD and anxiety. The innovative online mood-screening tool is offered in partnership with M3 which created this medically proven checklist for mental health well-being.

Visitors simply need to click on the box in the upper right corner of the Mental Health America home page labeled “How’s Your Mood Today” to start the three-minute self-assessment process. The customized assessment provides a score that a person can then share with his or her physician and monitor over time.

LINDA SEXTON’S MEMOIR REVEALS THE DARK TRUTH BEHIND HER MOTHER’S BRILLIANCE

A book review by Victoria Costello (originally published on Psychology Today.com). As someone who’s battled life-long major depression, I thought I knew enough about the depths of despair to which this illness can send you. And then I read Linda Sexton’s painfully explicit, at times claustrophobic, yet surefooted and ultimately redemptive memoir Half in Love, Surviving the Legacy of Suicide. When I put down Sexton’s book, I had a profound new understanding of the extent to which unipolar depression, my diagnosis, is the milder second cousin to the bipolar variety. This memoir leaves no doubt of the extreme danger conferred by the massive mood swings of bipolar disorder, particularly the high risk of suicide. It’s one thing to know it, it’s quite another to see it through Linda Sexton’s eyes as the child of a bipolar mother for whom death was both a demanding creative muse and Linda’s main rival for her mother’s attention.

Interestingly, Anne Sexton managed to include young Linda in her creative writing process, going so far as to arrange poetry writing lessons for her daughter. But the pull of death was something else entirely, first for the mother, and then, in a near repeat of the same tragedy, for the daughter who emulated everything about her. Linda Sexton begins her story on the evening of her first suicide attempt, when she takes narcotic pills and slits her wrists in the bath tub of her family home while her husband is away on business and her teenage sons sleep in their rooms down the hall. As she sinks into unconsciousness, Linda remembers the promise she made to her boys that she would never do to them what her mother had done to her, and then proceeds to nearly do it. The author describes her loss of resolve with heartbreaking honesty. “I was ready, at last, to cheat on love. Ready to renege on assurances that now felt as if they had been too easily given to everyone-children, husband, sister, father, friends. Immersed in communing with my mother, I became a small child that night, a vulnerable daughter. She seemed right then to hover in the room, guiding me. I knew that when I finished, she would be waiting to fold me into her arms, and I would go home with her one more time.”

The next scene, appropriately, brings us back to the morning in 1974, when, as a 21 year old college senior, Linda learns that her mother, by then a Pulitzer Prize winning cultural darling, has finally, after innumerable attempts, succeeded in killing herself by carbon monoxide poisoning in the family garage. Over the next several chapters, Linda recounts her later childhood and teen years at the hands of this often loving, but wildly inconsistent mother. By the time the author returns to the night of her own suicide attempt, she is forty-five years old, and we are not a bit surprised to learn that she has reached the same age as Anne Sexton when she took her life…so strongly has Linda brought us into her visceral experience of being the adoring, insecure daughter who identifies completely with a beautiful, vivacious, but helplessly narcissistic parent.

The fact that it is Anne Sexton’s bipolar disorder–never properly diagnosed or treated–producing this deranged parenting is never far from the reader’s consciousness. The daughter well understands her mother’s feelings of hopelessness; within months Linda receives the same diagnosis. Linda Sexton’s journey to recovery is well worth reading for itself. But because of her mother’s cultural significance, Linda’s story offers us other insights. After reading Half in Love, I re-read some of Anne Sexton’s poetry, and watched some videos of her readings from the 1960s, performances that are now easily accessible on You-Tube.

I also read with dismay the review given Half in Love in the New York Times in February of this year. While it is mostly positive, the reviewer ends bizarrely by lamenting that Linda Gray Sexton is not a carbon copy of her mother, writing: “There is, however, no getting around the fact that Sexton never becomes as compelling a character as her mother was… Even when she was sickest, Anne Sexton managed to create a vibrant world around herself, never losing her status as a figure to be reckoned with.” About Linda Sexton’s book this critic writes, “There is a surprising blandness to her sensibility, and her cause isn’t helped by overwrought language and hackneyed therapy-speak.” Well, gee, I thought, should we really be surprised that the story of someone in recovery isn’t nearly as “compelling” as that of someone who never leaves the path of self destruction; abandoning her children while self-medicating and, driven by her mania, giving riveting performances of suicidal poetry all over the world?

The poetry of Anne Sexton is startling and beautiful; just as she was. But what Linda’s story finally makes clear is that her mother could barely get to her desk, let alone write something beautiful when she was in one of her long stretches of depression, which would frequently go on for months. I couldn’t help but wonder…aren’t we beyond the idiocy that says mental illness and great art somehow need each other? There are numerous studies showing that although the mood swings of bipolar and the cliff-edged near psychotic thinking of schizophrenia can bring extra-ordinary creative insights, everything else about these diseases can extinguish the same insights There’s still the odor of romanticization here.

I highly recommend Half in Love, Surviving the Legacy of Suicide. The good news Linda Gray Sexton offers in her final chapter is the arrival of her own hard won stability. And then, in a touching and beautifully rendered scene, she shares the conversation she has with her two now grown sons, in which she asks their forgiveness and speaks openly about the illness for which they too are at high risk. The fact that this conversation happens at all offers real hope that the legacy of suicide will, at least in this family, finally be halted.

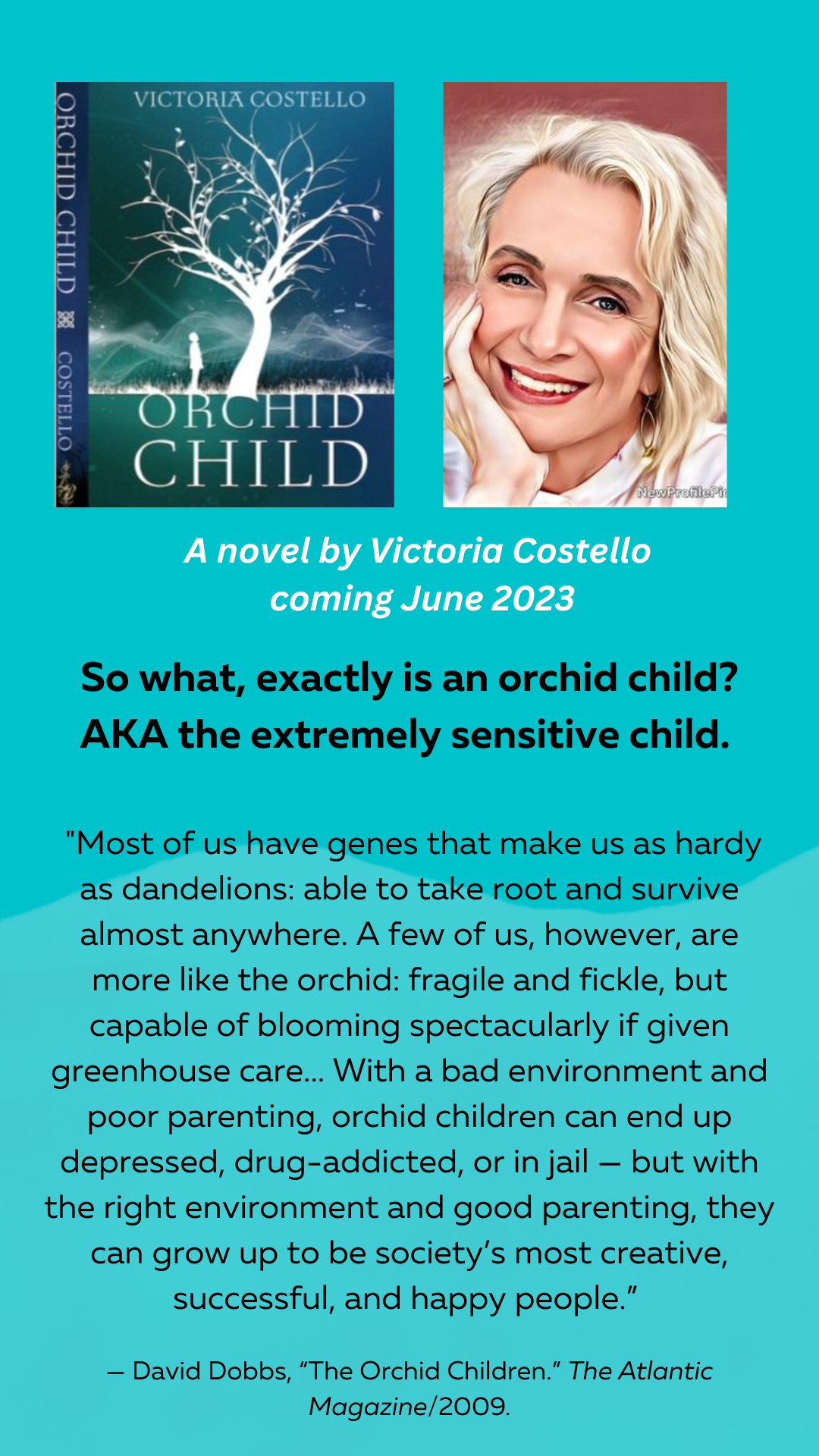

VICTORIA COSTELLO is an Emmy-award winning science journalist turned fiction writer. Her debut novel, ORCHID CHILD, forthcoming in June of 2023, explores the path of trauma across three generations in one Irish-American family and how the youngest member, its orchid child, stops the chain of suffering by tapping his neurodiversity and the ancient wisdom of his ancestors. Read more here.

Originally Posted on Mental Health Mom Blog April 7, 2014

Almost startling in its consistency, a new peer-reviewed study published in PLOS ONE (April 2, 2014) , a full decade after the often-cited McGill University metastudy on the relationship between mental illness and suicide risk, produced essentially the same major finding — within 2%. The Australian and American scientists responsible for the new research paper, titled The Burden Attributable to Mental and Substance Use Disorders as Risk Factors for Suicide: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010, compiled worldwide data from the World Health Organization (WHO) to show that 85% of people who die by suicide have a debilitating mental disorder. One difference: this study includes addiction as a major mental disorder, which reflects more recent classifications in the mental health field.

The underlying WHO data doesn’t fully represent mid to lower income countries so even this high a percentage linking suicide and mental illness no doubt underestimates the real numbers of people who die by their own hand in places where national and local health systems simply don’t count them. For better or worse, this research certainly covers most of us living in the US.

Sometimes the numbers provide important nuances to help us understand who, how, where, when and even why…

Nearly 1 million people complete suicide every year with over 50% aged between 15 and 44 years [14], [15].

Over 80% of suicides occur in low to middle income countries and close to 50% occur in India and China alone [15], [16].

the risk of suicide was 7.5 (6.2–9.0) times higher in males and 11.7 (9.7–14.1) times higher in females with a mental or substance use disorder compared to males and females with no mental health or addiction disorder

Suicide from firearms, car exhaust and poisoning are more common in high income countries and suicide from pesticide poisoning, hanging and self-immolation are more common in low to middle income countries [17].

There is also a telling graph of which disorders rank as the most and least dangerous in terms of suicide risk, with major depression leading the way:Lastly, the authors also looked at prevention strategies, and found that equipping general practitioners to diagnose and treat major depression had the highest value as a strategy, with a few caveats, as usual having to do with the quality of care. ” This was one of the few interventions for which there was good evidence of effectiveness as a suicide prevention strategy in a recent review by Mann and colleagues. That said, ensuring that care from general practitioners is evidence-based requires further consideration, given findings that rates of minimally adequate treatment for depression are lower among patients treated solely by general practitioners or in the general medical care sector, compared to those treated by specialist mental health providers.”

The unavoidable point: treatable mental disorders if left untreated put you at a much higher risk for suicide. What else is there to say?